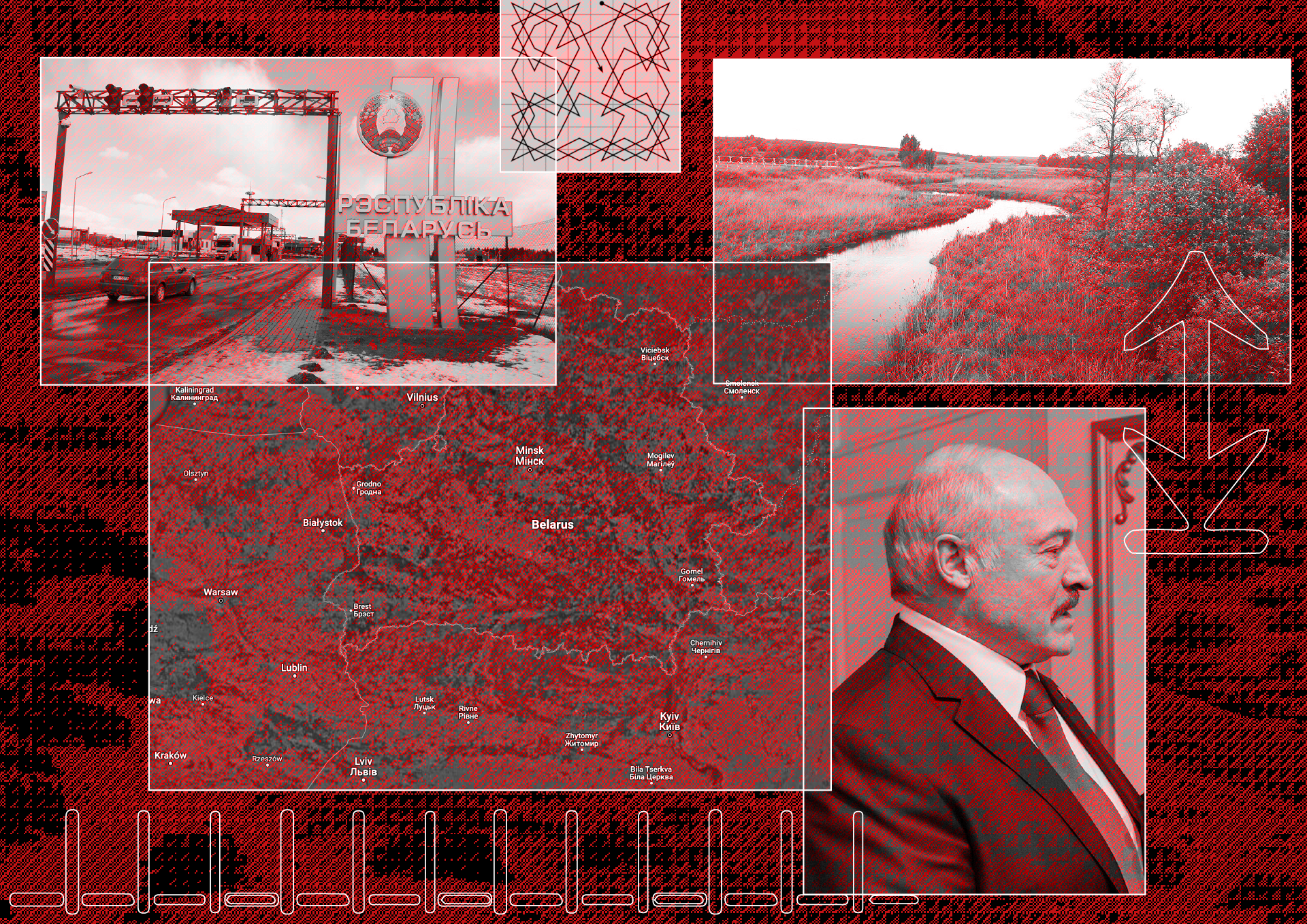

Migrants as Political Pawns: How Belarus is Trafficking Thousands of Migrants into the EU

Our first investigation into the border between Belarus and the EU.

By Eve Johnstone

cw: violence, sexual assault, xenophobia

In May 2021, the president of Belarus Alexander Lukashenko threatened to ‘flood the EU with drugs and migrants’. Over the following weeks, travel agencies across Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria began advertising that Belarus had launched a new tourist visa scheme. Included in the deal was transport to the Belarusian capital, Minsk, and guidelines on how to enter the EU through Latvia, Lithuania or Poland.

By November, thousands of predominantly Iraqi-Kurdish and Yazidi migrants were left stranded in forests at Belarus’ western borders. Reports of violent pushbacks from EU border guards proliferated across social media. Crucially, Belarus - the country that sponsored the mass migration - denied re-entry to those trapped between borders.

Despite couching his rhetoric in a vocabulary of human rights, what Lukashenko actually did was manufacture a political and humanitarian disaster

With thousands already stuck in appalling conditions, Lukashenko continued urging the migrant population to attempt illegal crossing. The president even visited a warehouse housing several thousand migrants in November and told the crowd: ‘If anybody wants to go West - that is your right. We will not try to catch you, beat you, or hold you behind barbed wire’.

Despite couching his rhetoric in a vocabulary of human rights, what Lukashenko actually did was manufacture a political and humanitarian disaster on the eastern borders of the EU. Politicians in the West have labeled Lukashenko’s actions as ‘hybrid warfare’, and the resultant situation on the Belarusian border a ‘humanitarian crisis’.

The Political Context

The EU and Belarus have shared a troubled relationship since the inauguration of Belarus’ first and only president, Alexander Lukashenko, in 1994. The president’s leadership is widely considered to be undemocratic and illegitimate, with reports of Belarusian authorities detaining thousands of protestors in the run-up to his sixth re-election in 2020. International monitors at the UN condemned the re-election as ‘neither free nor fair’. The European Council subsequently imposed restrictive measures on individuals involved in election misconduct and repression, including Lukashenko himself.

Lukashenko threatened that the West would ‘choke on these sanctions’, before rhetorically asking if the EU was trying to push ‘us and Russia’ to start World War Three.

In May 2021, further severe sanctions were placed on Belarus after national authorities fabricated a terrorist threat from Hamas - a Palestinian Islamic nationalist group - to force Ryanair Flight 4978 to land in Minsk. When the plane landed, dissident journalist Roman Protasevich who was onboard the flight was immediately arrested. The incident was branded a ‘state sponsored hijacking’ by Ryanair CEO Michael O’Leary, and the resulting sanctions, implemented by the EU, the US, and the UK, reportedly cost Belarus $10 million per month in lost revenue. Significantly, the only country that has openly supported Lukashenko is Russia; both the Russian President Vladimir Putin and Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov publicly defended the forced landing. This, alongside Belarus’ heavy reliance on Russia both economically and politically, led to accusations of Russian involvement in the notorious incident.

Despite the crippling economic sanctions placed on Lukashenko, the Belarusian president has shown no intention of reforming his ways. In a speech at his annual press conference in August 2021, Lukashenko threatened that the West would ‘choke on these sanctions’, before rhetorically asking if the EU was trying to push ‘us and Russia’ to start World War Three.

This is the story of how Belarus has become a pariah of the Western world, but also of how the EU Bloc’s increasingly securitised borders have left it vulnerable to hybrid forms of warfare, often at great economic expense. Most significantly, paying the human price for this are the migrants and asylum seekers who have been caught on the fringes of Europe with few means of escape or safety.

The Manufactured Crisis

The process by which migrants were lured into the crisis was manifold. Disinformation campaigns spread across social media claiming that it was possible to enter the EU through Belarus. Meanwhile, Iraqi and Belarusian travel agencies promoted ‘tourist trips’ to the country with the aim of attracting interested migrants. Belavia, Belarus’ national airline, increased the number of flights from the Middle East to Minsk from 17 to 40 a week.

Visa laws were then relaxed in August. Belarusian state-owned travel agency Tsentrkurort was granted the authority to issue visas through package deals. Migrants were given visas on the grounds of either ‘hunting’ or ‘business’ purposes, these being the only two reasons that allowed foreigners to enter Belarus under its own coronavirus restrictions.

According to investigations by Reform.by and The Dossier, migrants paid up to $15,000 USD to fly to Minsk, where they were transferred to hotels - usually as a part of the package - and then on to the border regions approximately 200 miles away. Once migrants arrived at various points along the border, Belarusian border guards destroyed parts of the dividing fence, and in some cases, drove shuttle buses along the border to find the best places to cross.

Those who managed to cross into Poland were met with physical abuse and were forced back to the border, despite announcing their intention to claim asylum - a clear breach of international refugee law.

Migrants were then left to face hostile opposition from Polish, Latvian, and Lithuanian border guards. A small fraction managed to enter EU territory. The Guardian reports that hundreds - and later thousands - of families were left to find shelter in the forests on the Belarusian border.

Doctors working on both sides of the border have reported treating migrants with acute and complex injuries, including broken bones and concussions from repeated beatings, dehydration, poisoning from drinking contaminated water, and even frostbite leading to amputation. Many migrants lived in the forest without shelter for weeks, having been pushed between the two countries upwards of 30 times.

As of October 2021, the crisis was mainly concentrated along the border with Poland. Polish border guards used water cannons and tear gas against migrants, and many were severely beaten by the Polish military during repeated pushbacks. Those who managed to cross into Poland were met with physical abuse and were forced back to the border, despite announcing their intention to claim asylum - a clear breach of international refugee law.

The situation reached a peak in November 2021, when a thousand migrants were being brought to the Polish border daily by Belarusian authorities.

By the end of 2021, Frontex reported that the total number of illegal border crossings into the EU via Belarus had increased by 1069% to 7,915 known cases. Additionally, over 40,000 attempted crossings had been intercepted and an estimated 15,000 migrants and refugees were reportedly stranded in Belarusian territory.

The number of recorded deaths by this time was 21, but humanitarian agencies have warned that the actual number is likely to be much higher.

EU Response

Once it became clear to EU authorities that Belarus was enabling irregular migration into its territory, a State of Emergency was declared in all three affected countries.

The EU allocated an initial humanitarian support package of €700,000 to humanitarian agencies in November 2021, aimed at ‘alleviat[ing] the suffering of people stranded on the border’, and brought in substantial legal support for affected countries in subsequent weeks.

On December 1st, the European Commission announced a package of ‘extraordianary and exceptional’ legal and practical measures, including increasing the registration period for asylum applications to 4 weeks (up from 10 days) and increasing the holding time for asylum seekers at the border from 4 to 16 weeks. Deportation processes were expedited and grossly simplified. These measures were denounced by Oxfam as placing ‘politics over peoples' lives’.

Amnesty International reported that migrants have been subject to arbitrary detention, inhumane treatment including tasering, forced sedation, beatings and sexual abuse.

The impacts of these harsh new laws were felt most in Poland, where asylum seekers and migrants reported being held for months in overcrowded and inhumane conditions, only to be transported back to Belarusian territory.

Poland, in particular, rapidly militarised its borders. The number of border guards quadrupled, and a 5.5m razor wire fence was built along its perimeter with Belarus at a cost of €353 million. Some have dubbed it Europe’s ‘new Iron Curtain’.

NGOs and human rights organisations have been banned from entering Polish borderlands, leaving only Polish civilians able to provide vital humanitarian support to migrants. In January, Medecins Sans Frontieres regretfully announced their withdrawal from the region, after several months of being denied access to those in need.

While NGO and journalist access to asylum-seekers within Poland has been limited, damning evidence of their treatment has emerged. From interviews following peoples’ release from Polish detention centres, Amnesty International reported that migrants have been subject to arbitrary detention, inhumane treatment including tasering, forced sedation, beatings and sexual abuse. They have also been denied access to asylum procedures and legal advice.

Despite criticism from Amnesty and other EU states on its treatment of refugees, Poland’s far-right Prime Minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, has refused to de-escalate at the border or to implement better care for detained migrants. Poland has now passed a law which enables migrants to be pushed back to Belarus regardless of their situation. This law ominously disregards the Geneva Convention and other international laws regarding the protection of refugees. Its very existence sets a dangerous precedent for the future of refugee protection, as it undermines the concept of non-refoulment - a principle that prohibits states from removing anyone who will face persecution from their territories.

What Is Belarus Set To Gain?

According to the EU Observer, Belarus’ most credible motive for creating a border crisis is to gain political leverage with the EU, perhaps with the aim of getting some of the crippling economic sanctions lifted. The EU inevitably requires cooperation from Belarus if it wants to quash the new migration route altogether, and therefore EU actors have been forced to reestablish communication.

State leaders from across Europe have indeed held meetings with the Belarussian president to discuss the worsening humanitarian situation. However, sanctions have not been removed.

As stated by Nikolay Mitrokhin, a political researcher at Germany’s Bremen University, ‘it is impossible to imagine that Belarus has provoked a military conflict with its neighbour without the support’ of Russia. In fact, Russian diplomats including Putin and Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov have advocated financial support for Belarus, the latter suggesting at a G4 Summit meeting that the EU offers Belarus a package similar to the €6 billion 2016 EU-Turkey deal.

Putin has blamed the West for the crisis, pointing to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan as the root cause. He also has criticized the response of Poland and the EU, saying that the beatings and maltreatment of the migrants stuck at the border ‘doesn't really tie in well with the ideas of humanity that supposedly underpin all the policies of our Western neighbours’.

According to the EU Observer, Belarus’ most credible motive for creating a border crisis is to gain political leverage with the EU

Videos highlighting the violence of EU border-guards have been widely disseminated in both Belarus and Russia. International commentators note these attempts to stoke anti-EU and anti-Polish sentiment tie in with Russia’s wider political opposition to the West. In turn, it also aids Russia’s justification of its invasion of Ukraine on the grounds of undermining EU hegemony.

EU Complicity

The migrant crisis in Belarus highlights the EU's vulnerability to the political weaponisation of its border. Migration policy is unharmonised across the EU bloc, and the Dublin Regulation - an EU law decreeing that the country where an asylum seeker first enters the EU has the responsibility to examine their asylum application - means that a small number of countries are overwhelmingly affected by migration flows.

This inequality has led to the emergence of populist anti-immigrant parties in countries such as Italy, Poland, and Germany. Because the EU does not have a united front for dealing with migration, and laws across different countries have become increasingly restrictive, migrants have been forced to take more dangerous routes. To the Mediterranean route and the Aegean route, we can now add the Belarusian route.

Although no one would hold Putin up as a model of humanitarian grace, his comments about the source of the issue lying with the EU hold some truth. The foreign policies of European states and the US were instrumental in causing regional instability in both the Middle East and West Africa. Increasingly restrictive asylum policies in Europe indicate that the West is willing to take little responsibility for its role in creating instability abroad.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen reminded delegates at the European Parliament that ‘as long as we do not find common ground on how to manage migration, our opponents will continue to target [us]’. Lukashenko’s weaponization of the EU’s eastern borders certainly evidences this point.

Today, most flights from Iraq, Syria and Turkey to Belarus have been terminated. However, the Belarusian route still exists; in fact, Amnesty has this month accused Latvian authorities of inflicting violence upon asylum seekers crossing its border with Belarus. Until the EU overhauls its dysfunctional asylum system, its adversaries will continue to weaponise the issue of irregular migration at the expense of both the European taxpayer and those fleeing danger.